- Home

- William Joyce

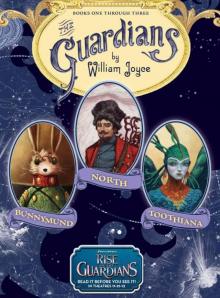

The Guardians

The Guardians Read online

Contents

Nicholas St. North and the Battle of the Nightmare King

E. Aster Bunnymund and the Warrior Eggs at the Earth’s Core

Toothiana Queen of the Tooth Fairy Armies

Contents

Chapter One

In Which the Great War Is Renewed

Chapter Two

Wherein Speaking Insect Languages Proves to Be of Value

Chapter Three

A Terrifying Walk in the Woods

Chapter Four

Out of the Shadows Come Deeper Mysteries

Chapter Five

The Golden Age

Chapter Six

Nicholas St. North (A Most Unlikely Source of Help)

Chapter Seven

Is Not Really a Chapter at All—Just a Piece of the Greater Puzzle

Chapter Eight

Where the Impossible Occurs with Surprising Regularity

Chapter Nine

The Battle of the Bear

Chapter Ten

In Which a Great Many Things Occur Swiftly

Chapter Eleven

In Which Wisdom Is Proven to Be a Tricky Customer Indeed

Chapter Twelve

Another Short but Intriguing Episode

Chapter Thirteen

The Warrior Apprentice Proves to Be Clever

Chapter Fourteen

Wherein Wizard and Apprentice Make Discoveries That Prove to Be Momentous

Chapter Fifteen

Partly Cloudy and Most Unfair

Chapter Sixteen

Anger, Age, and Fear Make an Unwanted Appearance

Chapter Seventeen

A Twist and Turn

Chapter Eighteen

Sly Is the Evil That Travels Unknown

Chapter Nineteen

The Telltale Hoot

Chapter Twenty

In Which a Twist of Fate Begets a Knot in the Plan

Chapter Twenty-One

Laughter Is a Bitter Pill

Chapter Twenty-Two

The Oddest Reunion

Chapter Twenty-Three

The Longest Night

Chapter Twenty-Four

The Journey’s End

To

Jack Joyce,

A fine, upstanding young rascal,

And to his sister,

Mary Katherine,

Who was fierce, fun, and kind

CHAPTER ONE

In Which the Great War Is Renewed

THE BATTLE OF THE Nightmare King began on a moonlit night long ago. In the quiet town of Tangle-wood, a small boy and his smaller sister woke with a start. Like most children (and some adults at one time or another), they were afraid of the dark. They each slowly sat up in bed, clutching their covers around themselves like a shield. Too fearful to rise and light a candle, the boy pushed aside the curtains and peered out the window, looking for the only other light to be seen during these long-ago nights—the Moon. It was there, full and bright.

At that moment a young moonbeam shot down from the sky and through the window. Like all beams, it had a mission: Protect the children.

The moonbeam glowed its very hardest, which seemed to comfort the two. One, then the other, breathed a sleepy sigh and lay back down. In a few moments they were once again asleep. The moonbeam scanned the room. All was safe. There was nothing there but shadows. But the beam sensed something beyond the room, beyond the cabin. Something, somewhere, wasn’t right. The beam ricocheted off the small glass mirror above the children’s chest of drawers and out the window.

It flashed through the village, then into the surrounding forest of pine and hemlock, flickering from icicle to icicle. Startling bats and surprising owls, it followed the old snow-covered Indian trail to the darkest part of the deep woods—a place the settlers feared and rarely ventured. Like a searchlight, the beam shot out into the darkness until it found a cave.

Our heroic moonbeam

Strange rocks, curling like melted wax, framed the yawning mouth of the cavern. The cave was thick with shadows that seemed to breathe like living things. In all its travels, the beam had never seen anything so ominous.

The moonbeam wavered and then—not sure if it was being brave or foolish—dropped down, following the shadows into the pit below.

The darkness seemed to go on and on forever. Finally, the moonbeam came to a stagnant pool. Black water reflected its glow, dimly lighting the cave. And there, in the center of the pool, stood a giant figure. He was denser and even darker than the shadows that surrounded him. Still as a statue, he wore a long cloak as inky as an oil seep. The moonbeam scanned the figure slowly, cautiously. When it reached his eyes, they opened! The figure was awake!

The shadows began writhing about at the feet of the figure, their low drone filling the air. They grew, crashing against the cave walls like waves against a ragged jetty. But they weren’t shadows at all! They were creatures—creatures that no child or Moon messenger had seen for centuries. And the moonbeam knew at once: It was surrounded by Fearlings and Nightmare Men—slaves of the Nightmare King!

The moonbeam paled and faltered. Perhaps it should have given up and fled back to the Moon. If it had, this story would never have been told. But the moonbeam did not flee. Inching closer, it realized that the phantom figure was the one all moonbeams had been taught to watch for: It was Pitch, the King of Nightmares! He had been pierced through the heart, a diamond-like dagger holding him pinned against a mound of ebony marble. Warily, the moonbeam crept closer still, grazing against the weapon’s crystal hilt.

But light does not go around crystal, it goes through it, and suddenly, the beam was sucked into the blade! Twisting from side to side, the moonbeam was pulled on a jagged course to the blade’s tip. It was trapped, suspended in Pitch’s frozen, glassy heart. Pitch’s chest began to glow from within as the moonbeam ricocheted about in a frenzy, desperate to escape. It was terrifyingly cold there—colder even than the darkest regions of space. But the moonbeam was not alone. There, just beyond the edge of the blade, in the farthest recesses of the phantom figure’s heart, it could see the spectral shape of a tiny elfin child curled tight. A boy? Hesitantly, the beam illuminated the child’s head.

That little ray of light was all it took; the spectral boy began to grow. He burst forth from Pitch’s chest joyfully, free at last! The moonbeam was thrown from side to side as the boy, with one quick tug, wrenched the radiant dagger from the cold heart that had trapped him. Bearing the blade aloft, with the moonbeam still caught inside lighting the way, the boy shot like a rocket straight up and out of the cursed cave and into the starry night. By the time his feet hit the snowy ground, he looked every bit like a real boy, if a real boy could be carved out of mist and light and miraculously brought to life.

Freed from the dagger’s impaling, Pitch began to grow as well, rising like a living tower of coal. Swelling to a monstrous size, he followed the boy’s illuminated trail to the surface.

Pitch and his Fearling Legions

Looking wildly up at the sky, Pitch sniffed the air in ecstasy. With one shrug and a toss of his midnight cloak, he blotted out the Moon. He crouched down and dug his fingers into the earth, letting the scents of the surrounding forest reach into his searching brain. He was ravenous, overwhelmed by a fiery hunger that burned him from within.

Breathing deeply, he trolled the winter wind for the prize he coveted, the tender meal he had craved even beyond freedom all those endless years of imprisonment down below: the good dreams of innocent children. He would turn those dreams into nightmares—every last one—till every child on Earth lived in terror. For that’s how Pitch intended to exact his revenge upon all those who had dared imprison him!

As glorious thoughts of revenge filled Pitch’s mind,

they ignited around him a cloud of sulfurous black. The cloud seeped upward from the seemingly bottomless pit of the cave. From that vapor, hurtling in all directions at once, came the shadow creatures—the Fearlings and Nightmare Men—thousands of them, horrendously shrieking. Like giant bats, they glided over the forest and beyond, invading the dreams of all who slept nearby.

By now the moonbeam was frantic. It had found Pitch! The Evil One! It had to return to the Moon and report back to Tsar Lunar! But it remembered the sleeping children back in their cabin. What if the Fearlings went after them? How could the moonbeam help if it was still trapped inside the diamond dagger? The beam bucked and strained, guiding the boy, who skittered along, light as air, back through the town, back to the small children’s window. They skidded to a stop.

A gathering of Fearlings

The spectral boy pulled himself up onto the windowsill. As he peered in at the children, somewhere in his heart an ancient memory or remembrance stirred of a sleeping baby and a distant lullaby. But the memory dissolved almost as soon as it appeared, leaving him feeling deeply and unexpectedly sad.

Something dark flashed past the boy and into the children’s room. Suddenly, two Fearlings hovered and twisted in midair above the sleeping brother and sister who turned restlessly, clutching at their quilts. Instinctually, the spectral boy leaped off the windowsill and snatched a broken tree branch from the ground, attaching the diamond dagger to its end. He aimed his gleaming weapon at the window.

The Fearlings shrunk back from the light, but they did not disappear. So, for the second time that evening, the moonbeam glowed with all its might. The brightness was now too much for the Fearlings. With a low moan, they twined and curled, then vanished, as if they had never been there at all.

The children rolled over and nestled into their pillows with a smile.

And after seeing those smiles, the spectral boy laughed.

Up on the Moon, however, there was no cause for laughter. Tsar Lunar—the one we call the Man in the Moon—was on high alert. Something was amiss. Each night he sent thousands of moonbeams down to Earth. And each night they returned and made their reports. If they were still bright, all was well. But if they were darkened or tarnished from their travels, Tsar Lunar would know that the children of Earth needed his help.

For a millennium all had been well and the moonbeams had returned as brightly as they had ventured forth. But now, one moonbeam had not returned.

And for the first time in a very long time, Tsar Lunar felt an ancient dread.

CHAPTER TWO

Wherein Speaking Insect Languages proves to Be of Value

IN THE FORESTED HINTERLANDS of eastern Siberia sat the little town of Santoff Claussen. There lived one of the last great wizards, Ombric Shalazar, and that morning, he was in deep discussion with a number of nocturnal insects, specifically a Lunar Moth, several fireflies, and a glowworm.

This was not unusual. Ombric could speak several thousand languages. He was fluent in the dialects of all manner of bugs, birds, and beasts; he could even speak hippopotamus.

As he switched from Lunar Moth to firefly, a group of village children, early for school, hovered nearby. Many of them had just begun to learn some of the easier insect languages (ant, worm, snail), and though moth and firefly were difficult (glowworm, even more so), they could tell from the tone of the conversation that something was very wrong indeed.

Ombric ponders

Ombric was generally a wizard of extraordinary calm. Nothing seemed to surprise him. How could it? He was the last survivor of the lost city of Atlantis! He was a man who had seen and done everything. He could communicate telepathically to his owls. Walk through walls. Turn lead to gold. He’d helped invent time, gravity, and bouncing balls! But today, as he talked to this cluster of insects, he seemed, for the first time that the children had seen, perplexed and worried. His left eyebrow furrowed into a frown. Then suddenly, he turned to the children and said something he had never said before: “No lessons today. You should return to your homes—now.”

The children were amazed. Even disappointed. Lessons were never canceled and rarely over early! Sometimes they went on for so long that Ombric would have to stop time for a bit so they could go on even longer. This always caused great excitement because everything Ombric taught them was, without fail, fun. Not only did he show them how to make water flow backward and to properly dam a stream, he also taught them how to climb most everything, build catapults, and, best of all, the secrets of the imagination. “To understand pretending,” Ombric was fond of saying, “is to conquer all barriers of time and space.”

In fact, all of their studies were focused on how to make anything they thought of—no matter how impossible or fantastical—come true. And so, dejected and uneasy about the change to their daily routine, the children trudged back to their homes. Some lived in trees, some underground, some half and half. For Santoff Claussen was unlike any other village in the world. Every home had a secret passageway or trapdoor or magic room. Telescopes, and retractable roofs made of evergreen sprigs were the norm. That was how Ombric had dreamed it should be. He wanted a village that seemed impossible.

From the time Ombric was a very young wizard, he had journeyed to every corner of the Earth in search of the perfect place to create a haven for fellow dreamers. But it wasn’t until he was nearly hit by a meteor (which, fortunately, exploded two hillsides over) that he found just the right spot. Barely acknowledging his close call, he had investigated the still-warm crater. There, at its exact center, was a lone sapling that had survived the crash. The sapling glowed with what Ombric instantly deduced was the energy of ancient starlight.

The splendor of Big Root

The wizard tended the little tree, and it grew—faster than he ever thought possible—into a wonder of nature. A wonder of the cosmos! It grew to the exact size of Ombric’s dream for it. And it formed its limbs, roots, and trunk so that Ombric could live inside. The first children to see the great tree had named it Big Root. And from this headquarters, Ombric welcomed all those with inquiring minds and kind hearts. Soon a small village sprang up. Ombric called it Santoff Claussen, an ancient phrase from Atlantis that meant “place of dreams.”

The wizard labored daily to make Santoff Claussen a perfect haven for learning—an enlightened place where no one would laugh at anyone (young or old), who dreamed of what was possible . . . and impossible. And so inventors, scientists, artists, and visionaries from across the globe were drawn to his village.

Ombric knew that not everyone felt the same way about learning. Why, look at what they had done to poor Galileo in Italy when he’d dared to suggest that the Earth revolved around the sun! So Ombric designed layers of magical barriers, one inside the other, to protect his village, and, like the Great Wall of China, it took him centuries to build.

First, he cultivated an encircling hedge of bracken and vines to guard the heart of Santoff Claussen. The ground around the village, rich with stardust, proved to be a fertilizer like no other, so thick vines sprang up, spreading as Ombric directed. They twined and twisted into a nearly impenetrable hedge, a hundred feet high, barbed with thorns the length of spears.

In spite of the thorns, however, strangers more interested in rumors of treasure than in learning made their way to Santoff Claussen. Like most master wizards, Ombric could conjure up diamonds and gems of eye-popping splendor as he pleased. He used them in spells and elixirs. Once used, they lost their gleam and had no further value. Yet rumors of his untold wealth persisted. Indeed, there was treasure in Santoff Claussen! It was just not the sort the treasure seekers coveted.

Still, they came, the storied riches too enticing for treasure hunters to resist. But when they were met by an enraged wizard, they started new rumors. They called Ombric a heretic, a warlock, and worse. They said he had stolen the souls of the people of Santoff Claussen and should be burned at the stake.

So Ombric conjured a second ring of defense—a great black bear, the

largest in all the Russias, whose courage and devotion were unquestioned. The bear would patrol to protect the village from anyone who might cause harm.

Then, on the outer rim, Ombric planted a third ring—majestic oaks, the largest in the world, whose huge roots could rise up and block the advance of any who tried to enter with evil intent. Ombric had to search through seven of his most ancient journals to find just the right enchantment to accomplish that feat!

And in case that was not enough to keep the intruders away, Ombric conjured up one more thing: a ghostly temptress with a beguiling smile. Adorned with what seemed like glittering gems, his Spirit of the Forest could lure visitors of an unkind or ignoble disposition to a particularly useful doom, turning them into stone, cursed forever to be a part of the village’s defenses.

Ombric’s efforts proved successful. Eventually, fewer and fewer villains came to Santoff Claussen, and the village was spoken about only in whispers by the outsiders who still remembered it was there. Haunted, they said. Bewitched. A mystery best left unsolved if you knew what was good for you.

Solving mysteries, however, was a favorite pastime of the villagers, the children especially. The one that had them most curious was how Ombric made his spells. They loved to visit him unannounced, hoping to catch him in the middle of inventing a new species of talking pig, or frogs who could shoot bows and arrows. Once there, they would listen to their teacher hold forth on any subject he happened to be investigating.

They inevitably gathered around Ombric’s table, where they’d poke and prod at the noisy gizmos and gadgets, bubbling vials of startling colors and shapes, globes of worlds known and unknown, clocks that could bend time, tools of bizarre and delightful functions, winged wind machines, weather manipulators, and magnifying lenses so powerful that they could see the secret writings of germs and microbes. And the books. Countless books. Mountains of books containing knowledge from the beginning of recorded time.

The Guardians: Nicholas St. North and the Battle of the Nightmare King

The Guardians: Nicholas St. North and the Battle of the Nightmare King The Lost

The Lost Buddy

Buddy The Guardians

The Guardians The Guardians: Nicholas St. North and the Battle of the Nightmare King; E. Aster Bunnymund and the Warrior Eggs at the Earth's Core!; Toothiana, Queen of the Tooth Fairy Armies

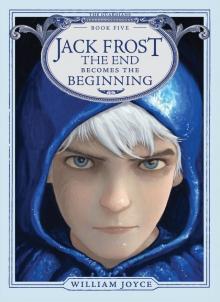

The Guardians: Nicholas St. North and the Battle of the Nightmare King; E. Aster Bunnymund and the Warrior Eggs at the Earth's Core!; Toothiana, Queen of the Tooth Fairy Armies Guardians Chapter Book #5

Guardians Chapter Book #5